Studying Statistics is Not a Shortcut to Studying Mathematics

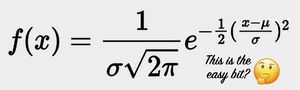

There is a great lie about which the educational-pedagogical establishment like to fool themselves with regard to mathematics. It is that statistics and probability are the easiest way to learn mathematics.

It’s possible that advocates of the approach genuinely believe in what they’re advocating. It’s also possible that a lot of those advocates know very well that what they’re advocating is nonsense, but they advocate it anyway because they believe nobody will learn mathematics unless they’re lied to about what it takes beforehand.

This Won't Hurt a Bit

This is not a sensible approach. Stephen King wrote about either a dentist or a doctor to whom King was sent as a kid who would always say “this won’t hurt a bit” before sinking the syringe home. The first two or three times King believed him - kids aren’t that bright, after all - but eventually the penny dropped and the only lesson King learned was to never, ever trust anything 1960s Maine's equivalent of Doctor Nick ever said.

The argument is that closest to real world that maths comes is in statistics, because statistics have real-world applications. Therefore, statistics provide a bridge for the learner from the real world into the mathematical world.

The problem arises because the worlds are not bridgeable. You can’t build a bridge into the sea, for instance. You can only bridge like-to-like.

That Certain Greek

Maths exist in its own world. The majority of the mathematical world as we know it was build by a Greek called Euclid about whom we know nothing except that everything we do in maths is build on the ideas first written down by Euclid over two thousand years ago. What is a point? Something of which there is nothing smaller. If there are a two points, what might connect them? Well, a line would connect them. And so on until you have worked the blueprint of the mathematical world.

Here’s an interesting thing about the second thing that Euclid ever defined, the line. No-one has ever seen one. If something has length but no breath, how can you see it? It has one dimension only. You’ve seen your teachers draw lines on the blackboards in your childhood but these were not lines, because they have breadth. The breadth of a stick of chalk, but breadth nonetheless. They were only representations of lines, but not the real thing. Nobody has ever seen a line, and nobody ever well - not in this world, certainly.

Foundations

Maths is built on foundations. First you define a point. Then you define a line to connect two points, and so one thing builds onto the next, and knowledge grows and grows. One of the things that makes maths hard, or a reason that people have difficulty with it in the past, is that at one point in their education they missed a bit, and the thing has never gelled since.

What particular bit they missed probably differs from person to person. So does why the missed it. Maybe the teacher didn’t do a great job of explaining it, maybe they weren’t paying attention, or maybe something else happened. Who knows. But once something is missing in the foundation the whole building becomes shaky.

Therefore, you start at the bottom when you start with mathematics. You do not start half-way up with statistics. The Educational-Pedagogical Establishment would be better telling people that yes, this will hurt, actually, but it won’t hurt for long and discomfort will be long forgotten by the thrill of the new worlds that are no open to you. Get learning.

Oh - speaking of maths and the real world, the Canadian writer Stephen Leacock wrote an excellent essay over one hundred years ago in which he brought those popular mathematics characters, A, B, and C, into the real world: https://gutenberg.ca/ebooks/leacock-literary/leacock-literary-00-h-dir/leacock-literary-00-h.html#A_B_and_C. Check it out. It's as fresh as if it were written yesterday.